Abstract

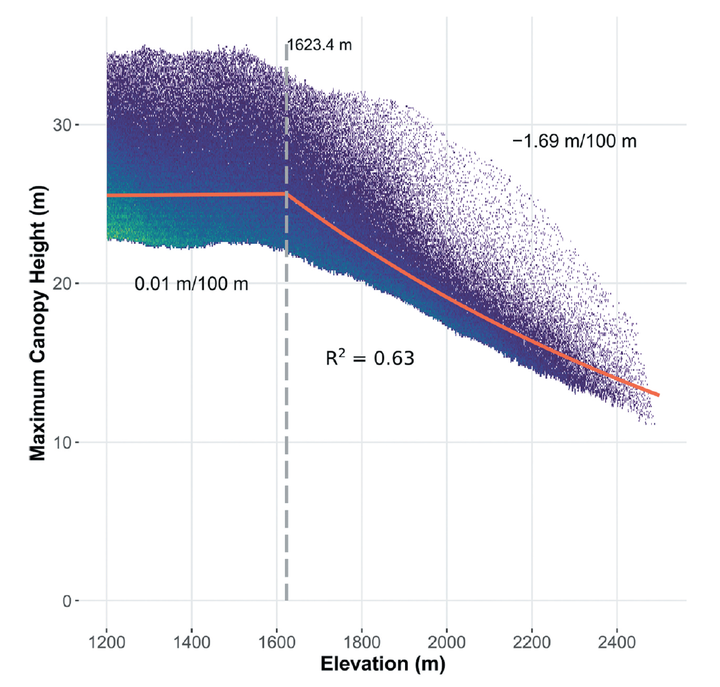

Canopy height is an excellent indicator of forest productivity, biodiversity and other ecosystem functions. Yet, we know little about how elevation drives canopy height in mountain areas. Here we take advantage of an ambitious airborne LiDAR flight plan to assess the relationship between elevation and maximum forest canopy height, and discuss its implications for the monitoring of mountain forests’ responses to climate change. We characterized vegetation structure using Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) data provided by the Spanish Geographic Institute. For each ALS return within forested areas, we calculated the maximum canopy height in a 20 × 20 m grid, and then added information on potential drivers of maximum canopy height, including ground elevation, terrain slope and aspect, soil characteristics, and continentality. We observed a strong, negative, piece-wise response of maximum canopy height to increasing elevation, with a well-defined breakpoint (at 1623 ± 5 m) that sets the beginning of the relationship between both variables. Above this point, the maximum canopy height decreased at a rate of 1.7 m per each 100 m gain in elevation. Elevation alone explained 63% of the variance in maximum canopy height, much more than any other tested variable. We observed species- and aspect-specific effects of elevation on maximum canopy height that match previous local studies, suggesting common patterns across mountain ranges. Our study is the first regional analysis of the relationship between elevation and maximum canopy height at such spatial resolution. The tree-height decline breakpoint holds an intrinsic potential to monitor mountain forests, and can thus serve as a robust indicator to appraise the effects of climate change, and address fundamental questions about how tree development varies along elevation gradients at regional or global scales.